This week, we experienced another national paroxysm of “controversy”, the result of which is that a few more formerly obstinate people admitted what millions already found obvious: Donald J. Trump is a hyper-combative, utterly incompetent, ignorant narcissist who cannot do the job he finds himself in.

Also, he may or may not have proven himself to be a racist and Nazi sympathizer, though neither of those possibilities is nearly as important to the world as his utter incompetence.

On the plus side, a few monuments to the Confederacy have been torn down, thereby bringing the Civil War one baby step closer to conclusion, only 152 short years after the last shot was fired.

Also, in some circles traveled only by the 1% , it has now become de rigueur to prove your bona fides on the subject of race by making some sort of gesture or speech about it, which doesn’t help all that much but doesn’t hurt either.

More than 40 years after the death of Tom Yawkey, Red Sox ownership is making little tiny noises about finally doing the right thing concerning the “legacy” of Tom Yawkey: killing it dead.

Yawkey bought the Red Sox for himself a few days after he turned 30 years old in 1933 for $1.25 million, thereby sentencing the team and its die-hard fan base to decades of mediocrity. Yawkey had inherited $40 million from the lumber and iron empire built by his grandfather, and could finally access the money, having reached the age specified in the will.

Today, $40 million doesn’t buy that much. Maybe the privilege of watching David Price nurse a hangnail on the bench for two years, or maybe watching Pablo Sandoval eat hamburgers in the minors before recognizing you made another small mistake. But in 1933, it was real money.

Yawkey never earned or produced anything on his own, and treated the Red Sox as a private club, often taking batting practice with “his boys”.

He died in 1976, a year after the greatest World Series ever played, in which the Red Sox lost the seventh game and came up empty for the third time on his watch. They were one player short of success yet again. The next year, Boston re-named part of Jersey St., on which Fenway Park’s main entrance sits, to Yawkey Way in honor of the great man. It’s been Yawkey Way since then.

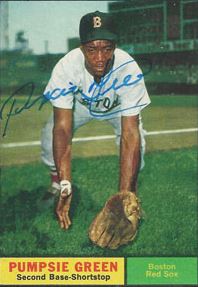

In his day, most people in Boston thought Yawkey was a peach of a guy, and most had no problem with his views on black people. He didn’t like them. The Red Sox were the last team in baseball to put a black player on the field, waiting until 1959, and they did so half-heartedly. Pumpsie Green was the man’s name, a .246 hitter with zero power over his five year career.

The Red Sox had the chance to sign Jackie Robinson and they passed. They did give him a tryout in 1945. A newly elected city councilman, Isadore Muchnick, campaigned to bring black players to Boston, and refused the usual formality of granting permission for the Red Sox and Braves to play on Sundays, unless they gave some guys from the Negro Leagues a tryout.

A day before the 1945 opener, Yawkey had Jackie Robinson, then of the Kansas City Monarchs, take the field for a look, along with Marvin Williams and Sam Jethroe. “We knew we were wasting our time”, Jackie said years later. No one from the press was there, and the whole charade lasted just a few minutes. It ended when someone from the stands yelled out. “Get those n—ers off the field”.

In 1945, the Red Sox weren’t alone in their antipathy. But in 1949, two years after Jackie was already in the majors and the direction of history was clear, the Red Sox passed on a 17-year-old prospect named Willie Mays, who they could have signed for $4500.

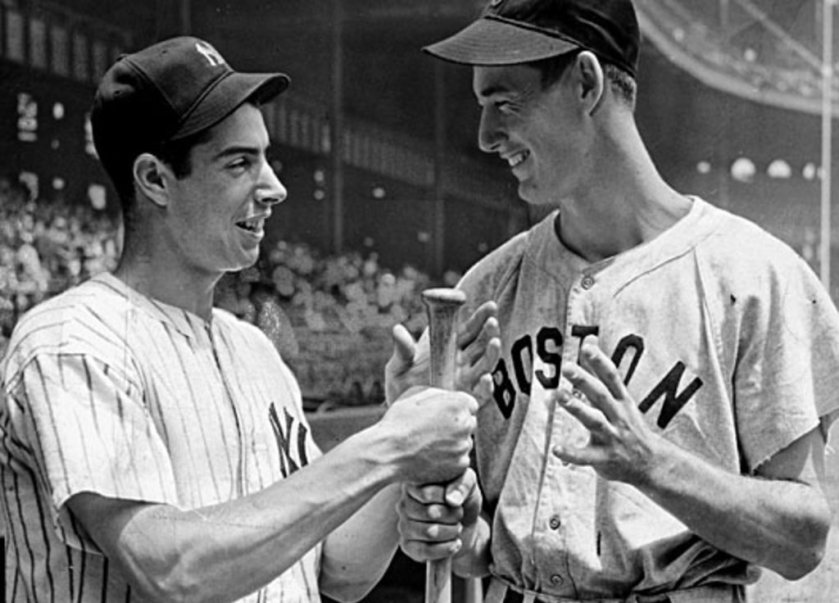

In the 1950’s, the Red Sox could have, and should have, had Ted Williams in left, Willie Mays in center, and Jackie Robinson at second. But Yawkey was too smart for that. Why try to win games with guys you don’t like when it’s so much more fun to relax with the guys you like?

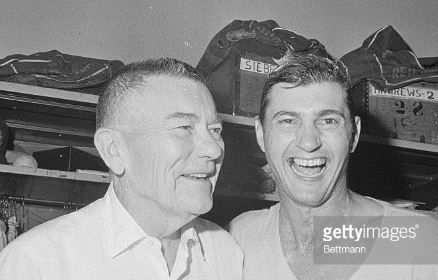

The above picture is Yawkey and Carl Yastrzemski, one of his favorites, after the “Impossible Dream” Red Sox backed into the 1967 World Series, surviving the closest pennant race in history.

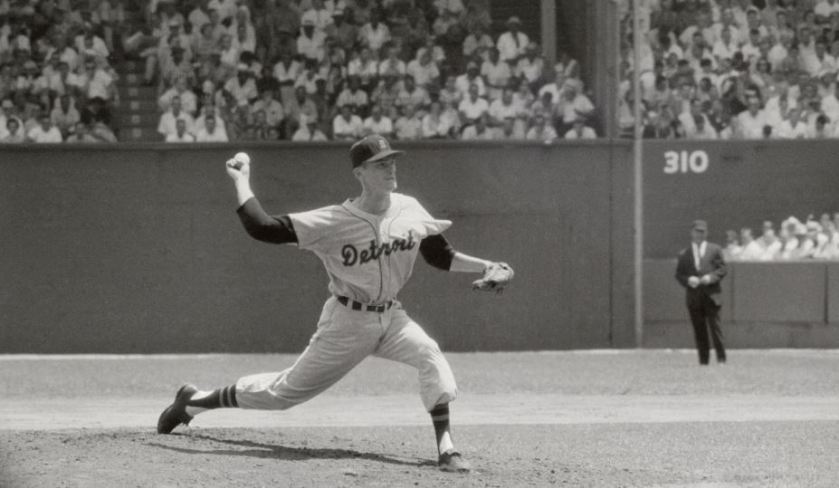

Yaz had a season for the ages, playing a supernatural left field all year while winning the Triple Crown and M.V.P. Wow. He played great in the Series, too, hitting .400 with three home runs and an On Base Percentage of .500. He carried the team into the seventh game, where the Red Sox put their Cy Young winner, Gentleman Jim Lonborg, on the mound with only two days rest to face the immortal Bob Gibson. Gibson, of course, cruised to his third win of the Series, striking out ten and giving up only three hits, and ended the Red Sox season in the predictable fashion.

But a good time was had by all, right?

The Red Sox were short just one player, as usual. Just one Bob Gibson. Or Jackie Robinson. Or Willie Mays. And it took another 37 years on top of that to finally get over the hump.

Now John Henry, principal owner of the Red Sox, is entertaining suggestions for re-naming Yawkey Way. I think “Willie Mays Avenue” would work.

My plan would be that the next time I’m down there on game day, and I overhear some kid saying to his father, “Dad, why is this ‘Willie Mays Avenue’? Willie never played here!”, I’ll look at them both sadly and say, “Exactly.”